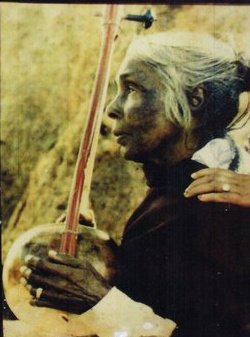

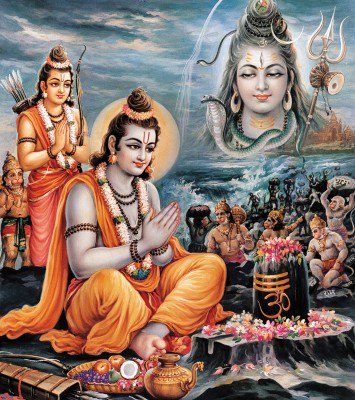

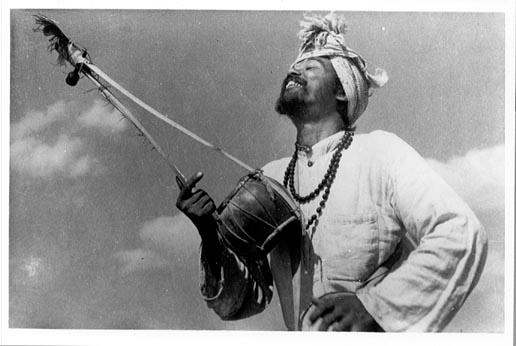

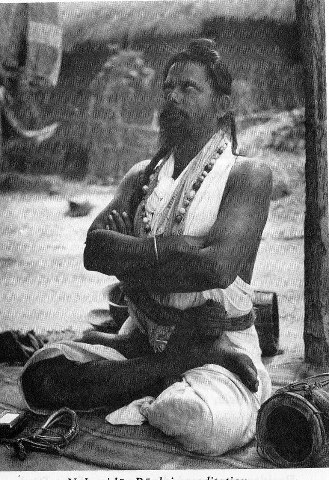

We crowded into the small dark room and sat shoulder to shoulder. The ceiling was covered with years of soot so thick that black stalactites had formed. My eyes teared from the fumes of incense and the yak dung smoke leaking from a crude wood stove. In the dark corner, light spilled from the doorway illuminating an ancient face, deeply etched from the harsh Tibetan life at 14,000 feet. There, leaning back in her meditation box was Sherab Zangmo spinning her prayer wheel.

sherab-zangmo-by-james-gritz

When Sherab Zangmo was a young nun, during a dark retreat (a Dzogchen practice of staying in total darkness for 49 days and nights), she had a vision of Yeshe Sogyal, Padmasambhava’s principle consort.

“Three times she offered me mudras (hand gestures) and then she became Tsang Yang Gyamtso (the student of the first Tsoknyi Rinpoche who started Getchak Nunnery). He came to rest on top of my head and then he dissolved into my body, speech and mind. We became one. I cried and cried. That moment I had a direct experience of the nature of my mind. I have had many experiences, good and bad, but my mind has remained stable, neither good nor bad.”

Enthralled with the concept of seeing the world through enlightened eyes I asked Sherab Zangmo, “Can you describe your perception of the world?”

She replied, “What arises in my mind now is the thought to benefit others. On the other hand, I don’t cling to appearances as real, in the way that others do.”

Wangdrag Rinpoche, the head of Getchak nunnery, asked her, “Do they appear like a dream?”

“Yes, they appear illusory, like a dream,” she said.

When Sherab Zangmo died a few months ago the nuns reported that her heart stayed warm several days after her death. The Tibetans call this tugdam — they say it sometimes occurs after the death of highly realized beings.

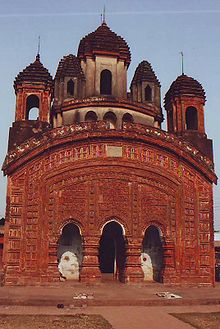

In 2005 I traveled with Tsoknyi Rinpoche III along with a small group students and a film crew to Nangchen, Tibet. Nangchen is located in the most southern part of the Qinghai Province of China. The first Tsoknyi Rinpoche was the root lama or principle teacher to the Nangchen nuns. He was a forward thinker and had the desire to create the same opportunity for women to practice and attain realization as the monks had. He had instructed his closest disciple, Tsang Yang Gyamtso, to build a series of nunneries to fulfill this vision.

We had traveled over a thousand kilometers from Xining by jeep south along the “National highway”. This was a ride from Hell that we thought we would never survive.

It took over 18 hours to get to Jekyundo. After a couple of days in Jekyundo, we made our way to Sechu. From there we traveled through the countryside crossing rivers over fragile, worn-out wooden bridges, slipping and sliding along the grassy slopes to a tent camp where several nuns and a small Khampa group outfitted us with horses. They led us for another eight hours across the high mountains of the Tibetan plateau. We arrived at Getchak greeted by the sound of Tibetan horns and cymbals. The nuns were dressed in their finest dakini robes.

Getchak consists of a large central abbey and a number of small earthen huts where up to a dozen nuns will live and practice together. The Nangchen nuns follow the tantric practices based on the teaching of the first Tsoknyi Rinpoche, who was considered an emanation of Ratna Lingpa. Tsoknyi Rinpoche III has characterized the heart of their practice as devotion and “pure perception.” What is most impressive with the nuns, said Tsoknyi Rinpoche, is their determination. Many nuns do three-year retreats, nine-year retreats, and even life-long retreats. A nun on retreat will practice day and night sitting in a wooden box that is only large enough to sit cross-legged. There is not enough room to lie down to sleep. A typical day begins at 3:30 in the morning and will include four three-hour meditation sessions. They will continue practicing dream yoga throughout the night.

In Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche’s memoirs, Blazing Splendor, he recalls the tummo (inner heat) practice of the Getchak nuns renowned throughout Tibet. In the middle of the Tibetan winter hundreds of nuns show their mastery of the practice called “the wet sheet.” Beginning at midnight they dip sheets in buckets of water melted from snow and wrap their naked bodies in the wet sheets. In his book, Tulku Urgyen describes seeing the misty vapors evaporating as the sheets dry from the body heat of a long line of nuns while they walk in eight directions around the monastery.

Because Sherab Zangmo was a woman there won’t be anyone looking for her reincarnation. Because she was an old nun living in a remote region of eastern Tibet and because she never traveled to the west or went on teaching tours there will probably be little, if any mention of her.

When we left Sherab Zangmo her prayer wheel was spinning. She was reciting the Vajrasattva hundred-syllable mantra, emanating prayers of peace and power that came from a lifetime of practice.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed