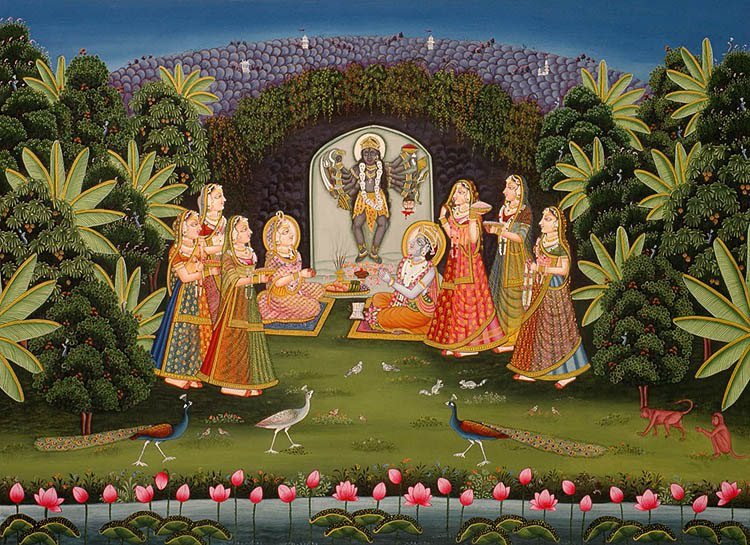

The incredible diversity of cultural practice and the bewildering plurality of aesthetic style and sensibility across South Asia might presuppose an indecipherable state of ongoing chaos. But there is, possibly, an invisible thread, an intangible pattern and purpose running through it.

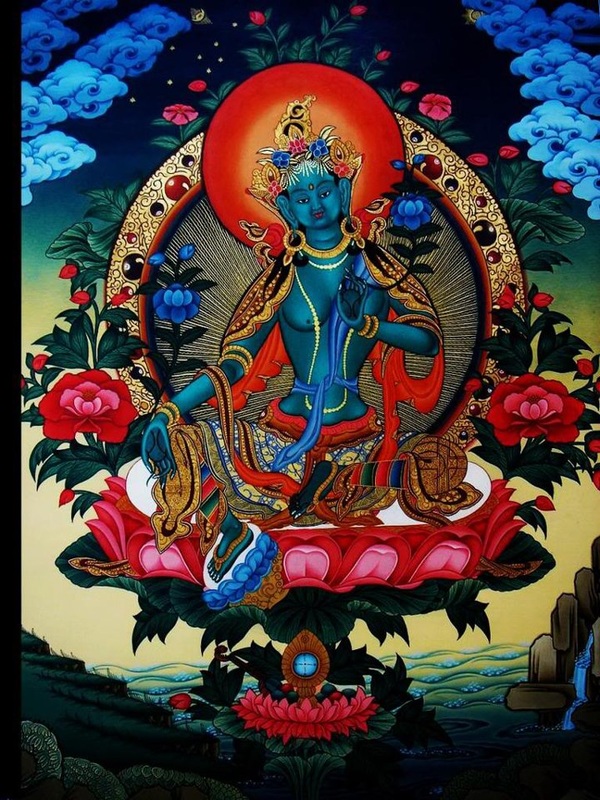

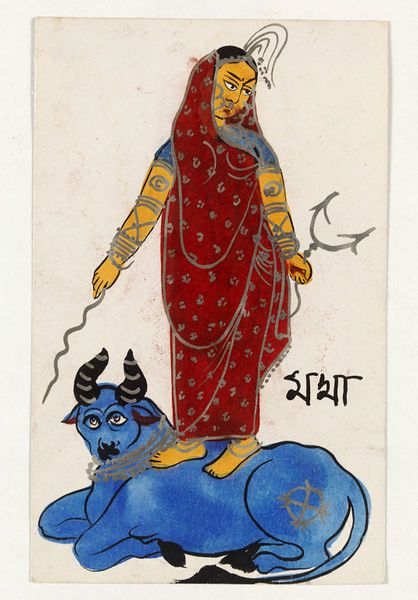

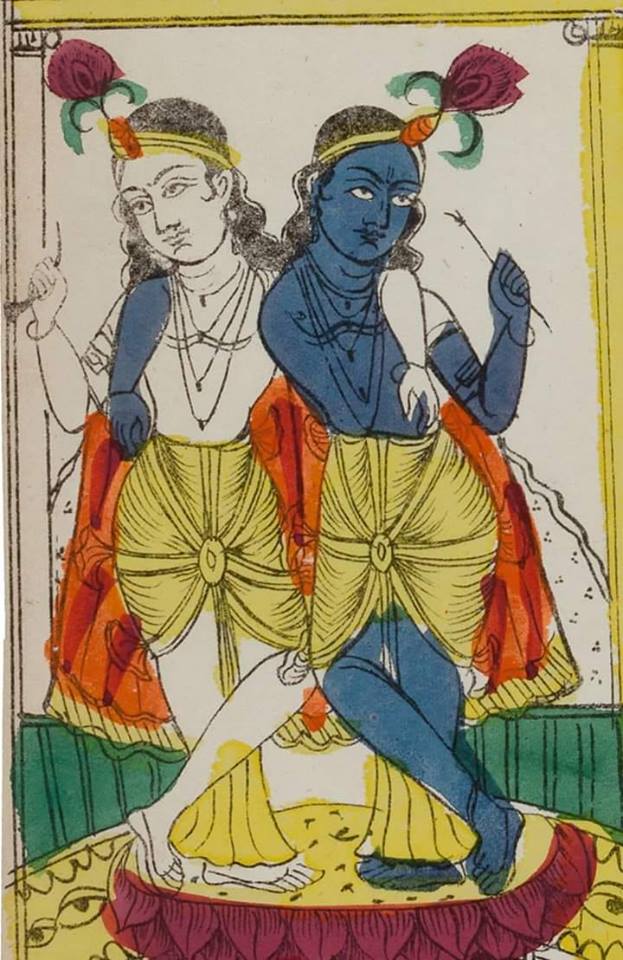

Through its ancient, continuous and assimilative cultural history, India has transmitted aesthetic theories and critical traditions—folk, tribal and classical—across its living artistic traditions. Such shared narratives and representations raise the human capacity of empathy and community understanding, and help in expanding individual struggles to a larger scale of understanding.

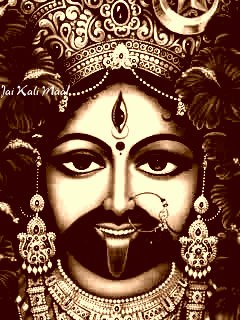

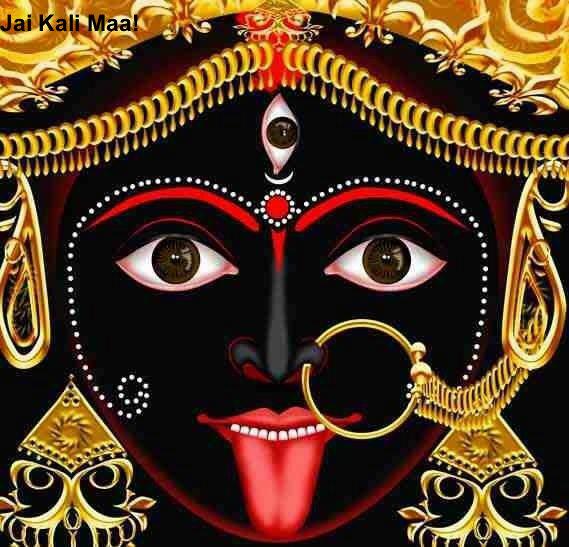

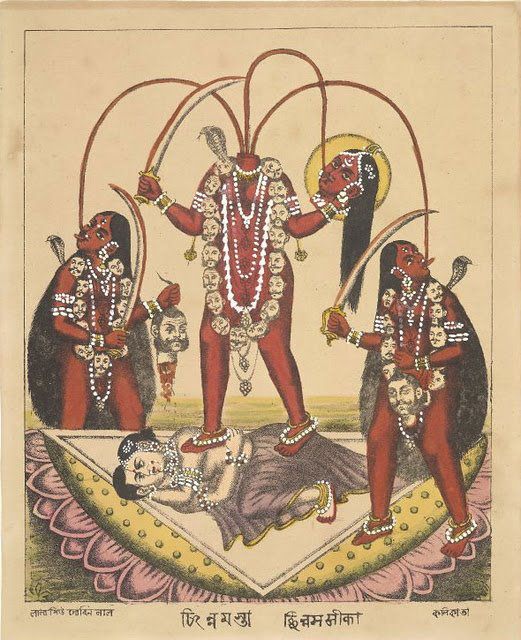

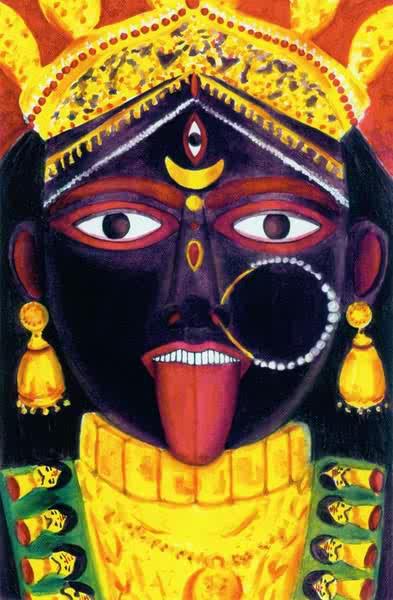

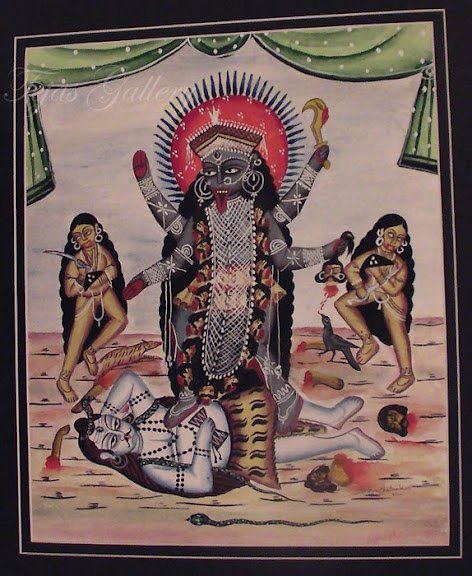

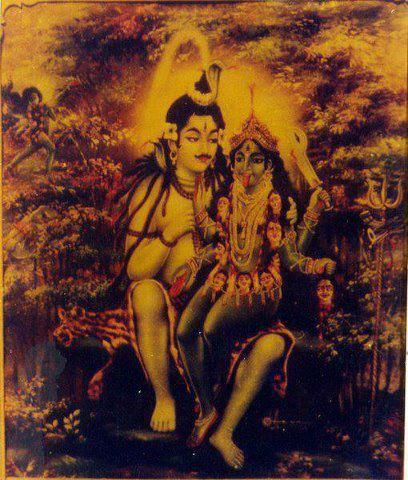

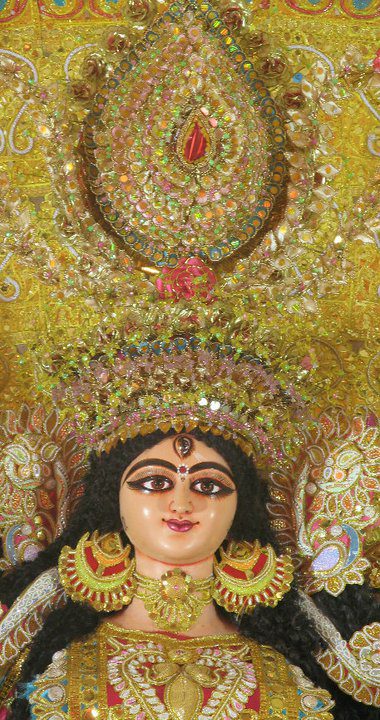

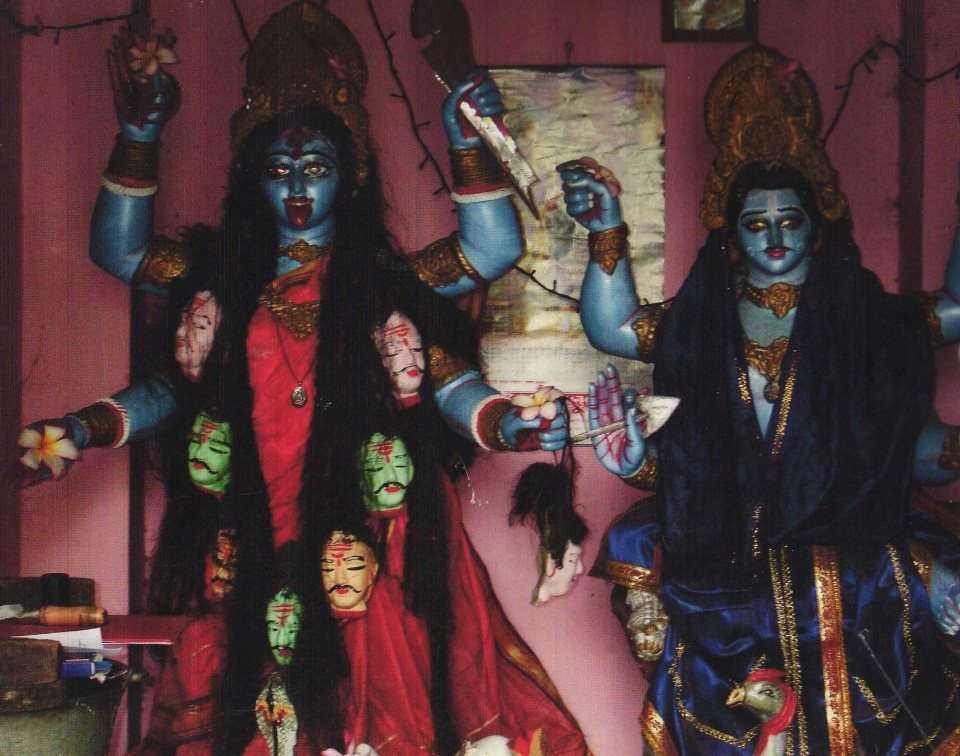

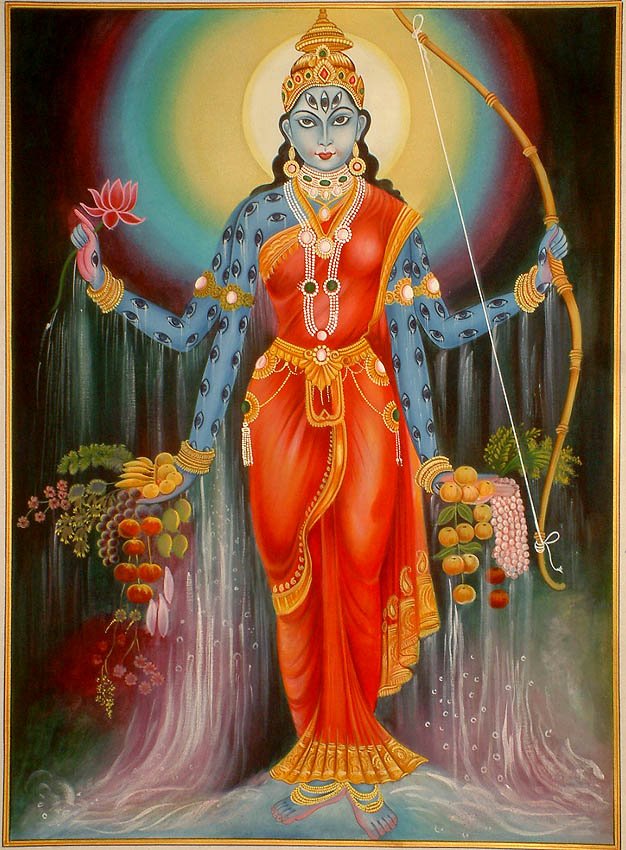

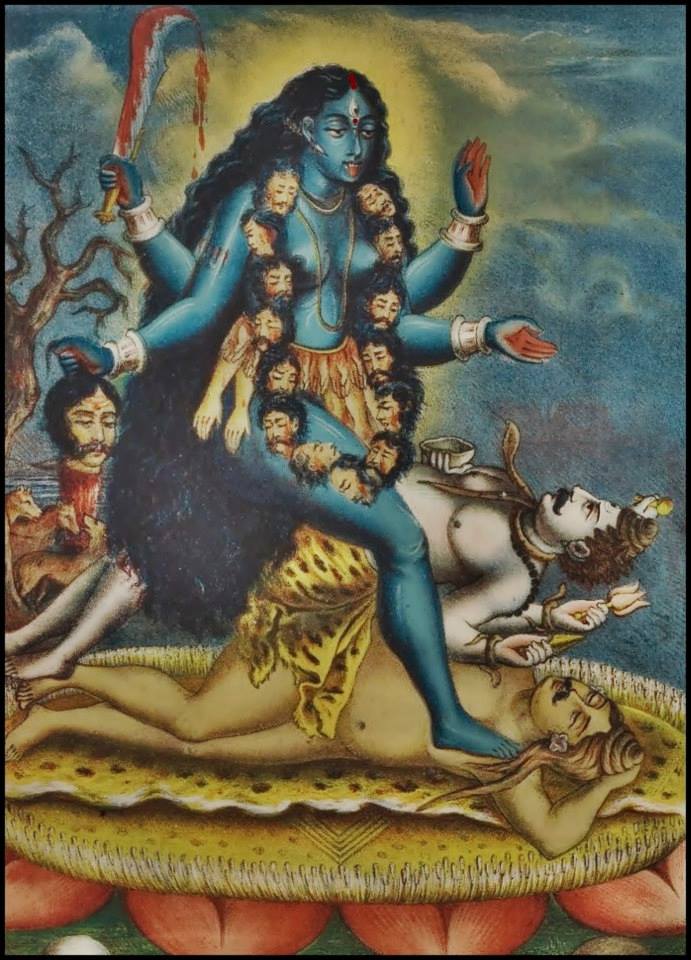

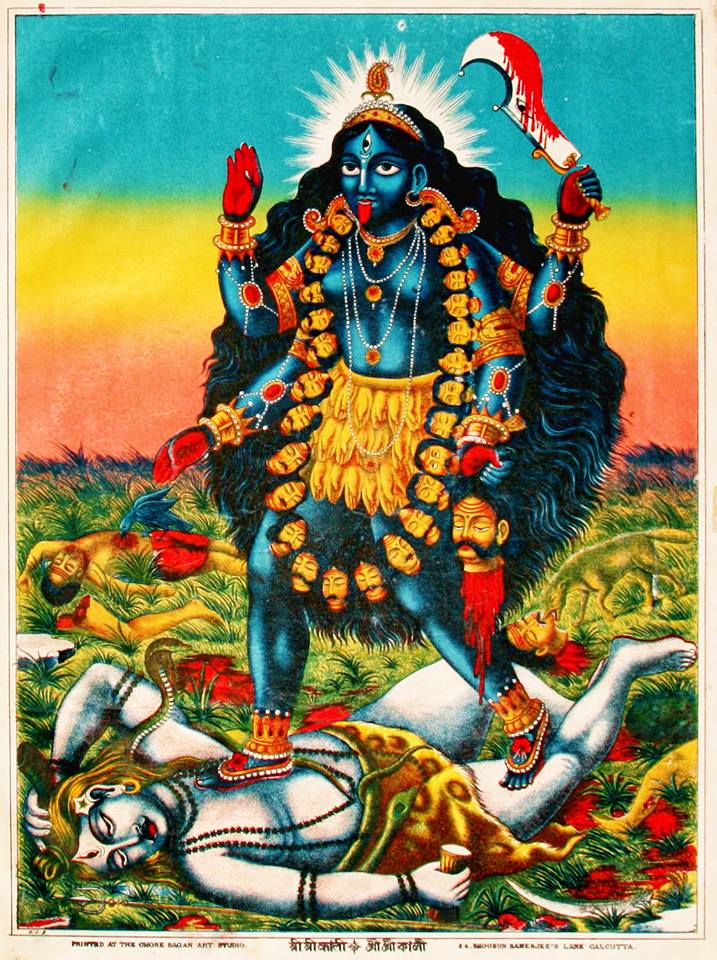

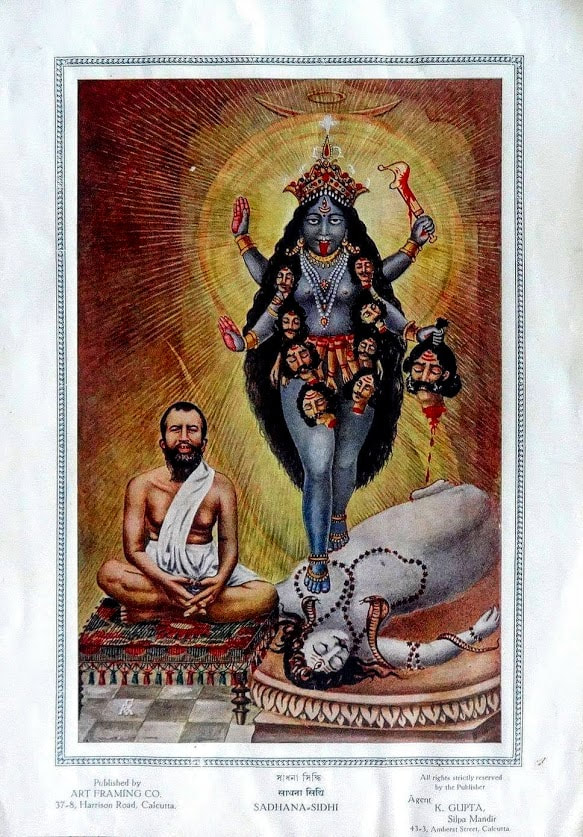

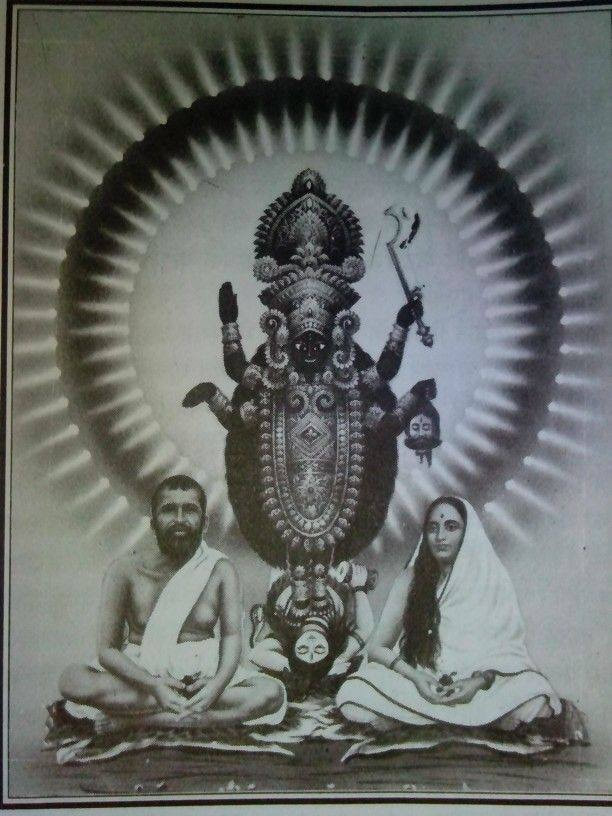

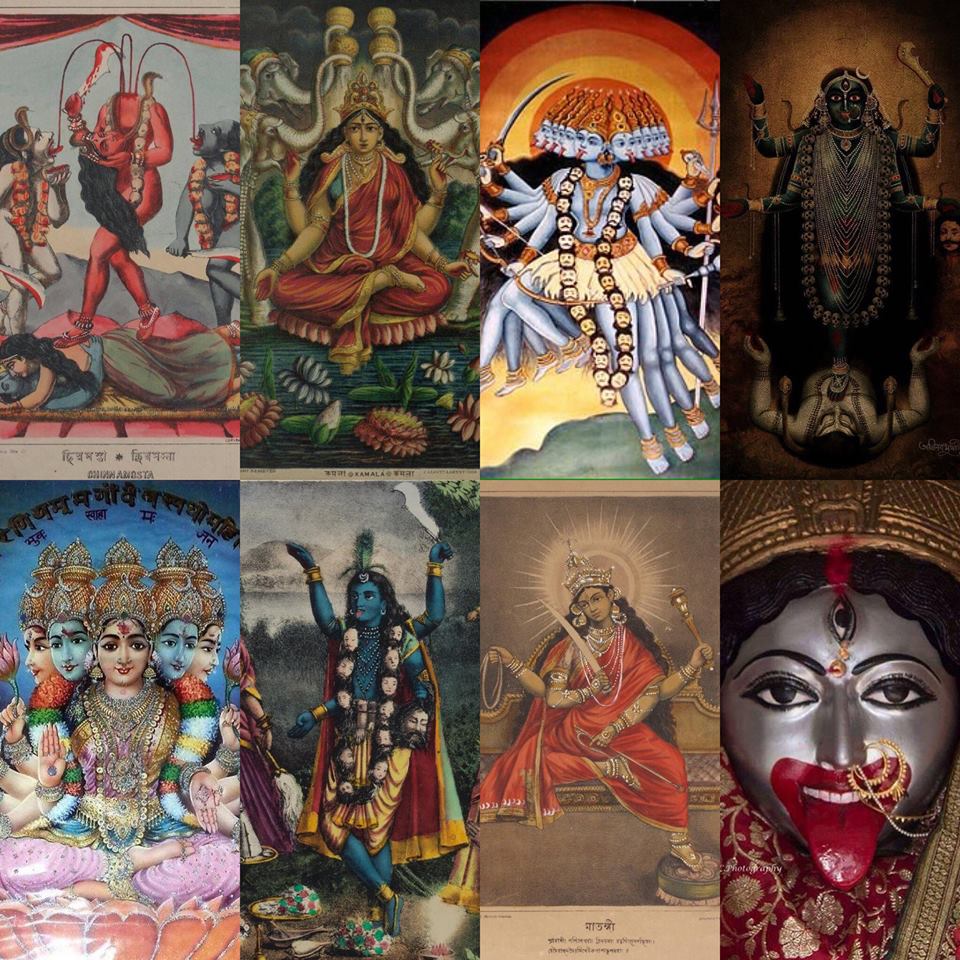

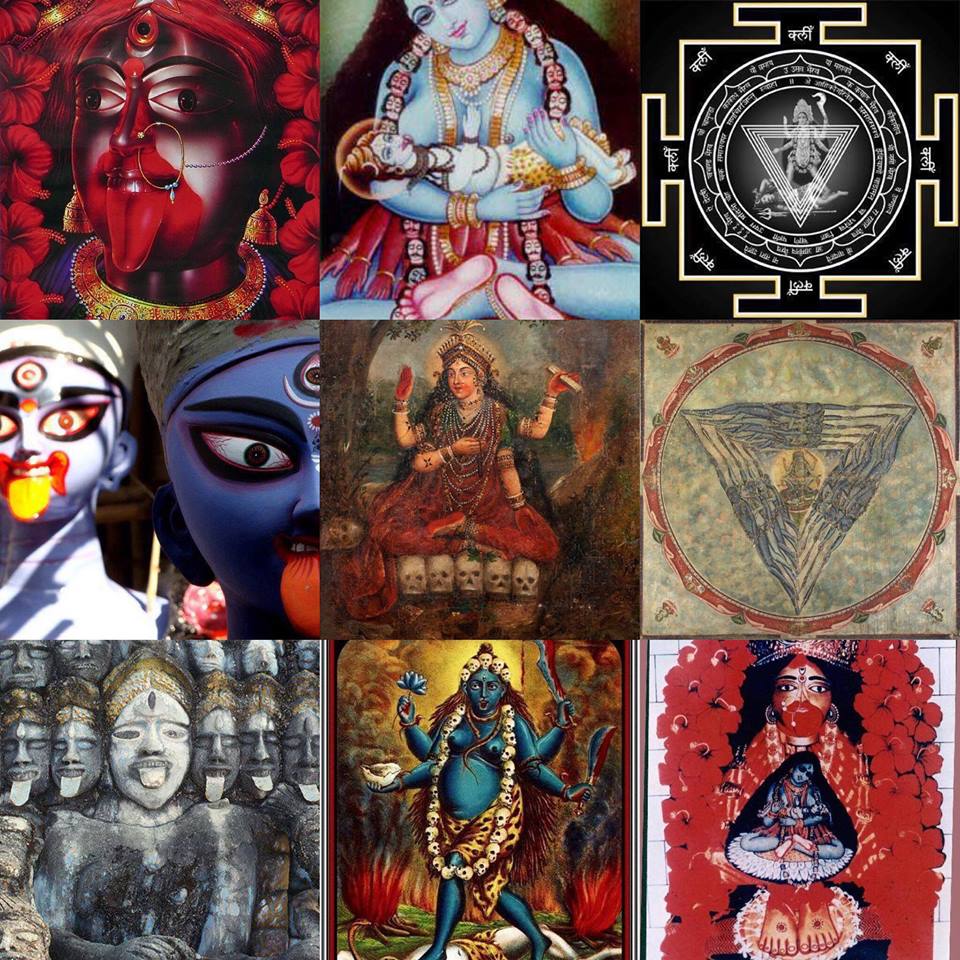

As a discipline, traditional subcontinental aesthetics was thought to be complex, subtle, and inclusive of both folk and tribal (desi) and classical (margi) traditions. It was said to incorporate the gamut of human feelings and emotions, accepting both the beauteous and the ugly and the refined and the vulgar.

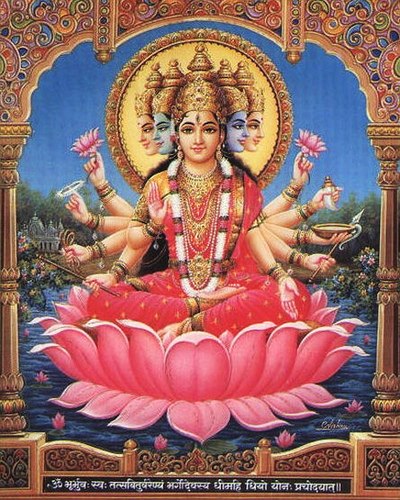

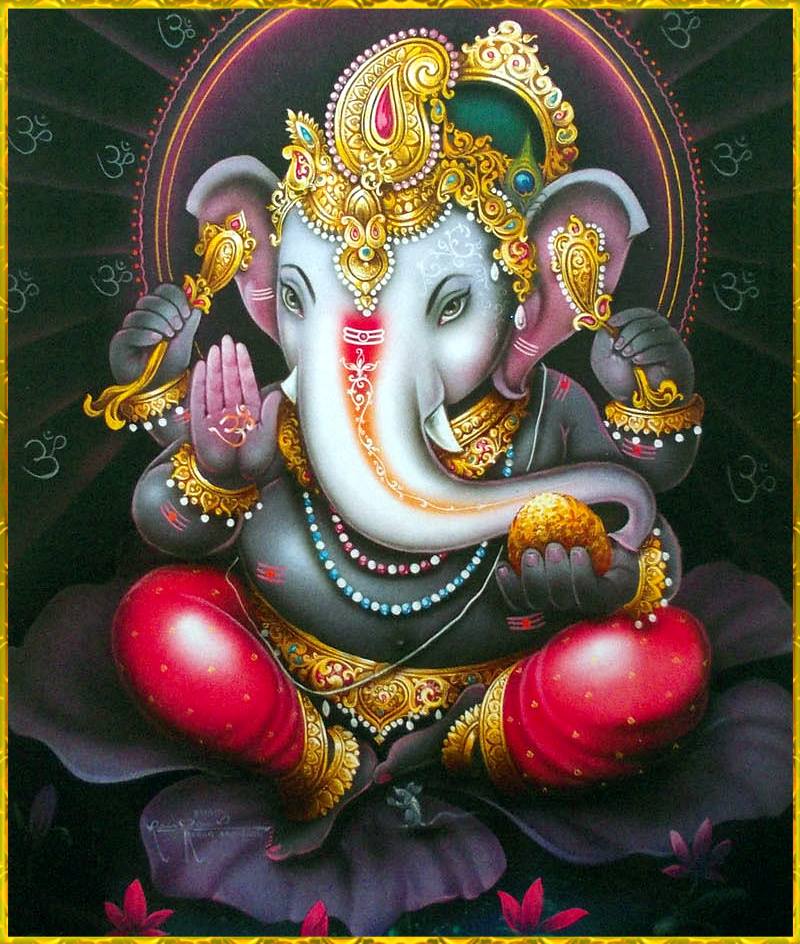

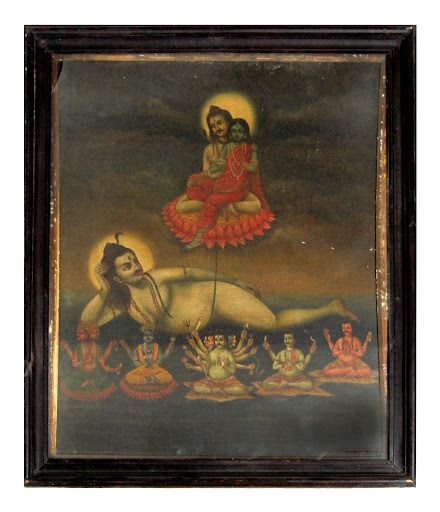

The Natya Shastra is among the many canonical texts claiming or aspiring to be in the category of the Fifth Veda, or the Pancham Veda. The God of Creation, Brahma, is said to be the originator of this work. It is also said to have been meditatively culled from the Rig Veda for literary text, the Sama Veda for music and dance, the Yajur Veda for acting and theatrical representation, and the Atharva Veda for aesthetic mood and theory.

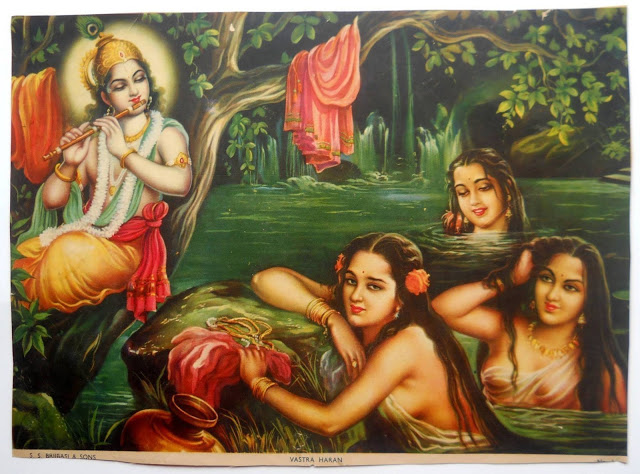

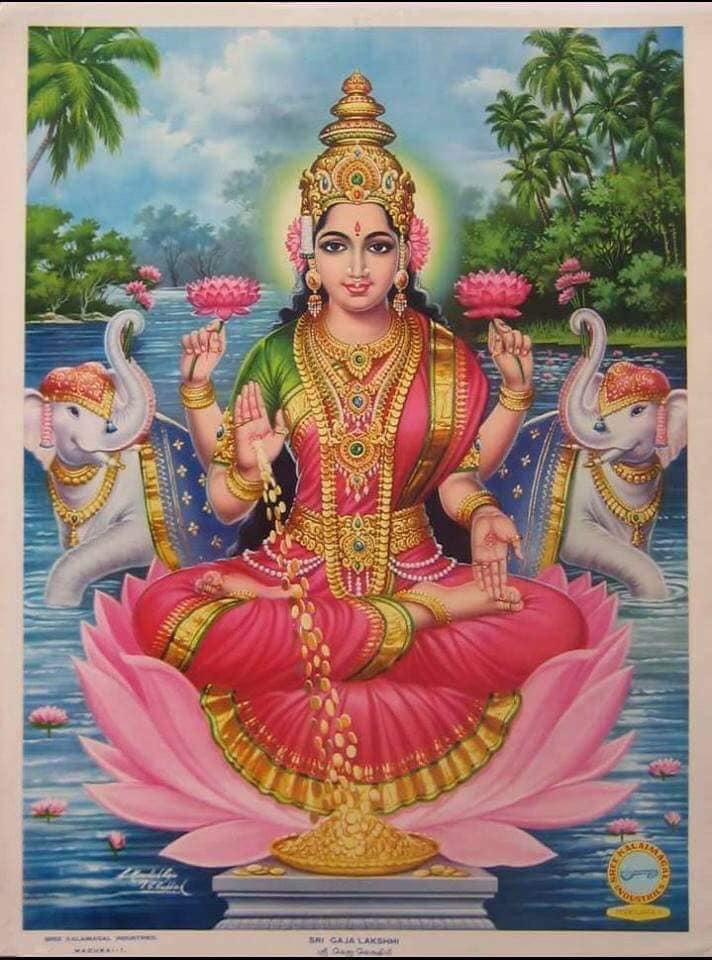

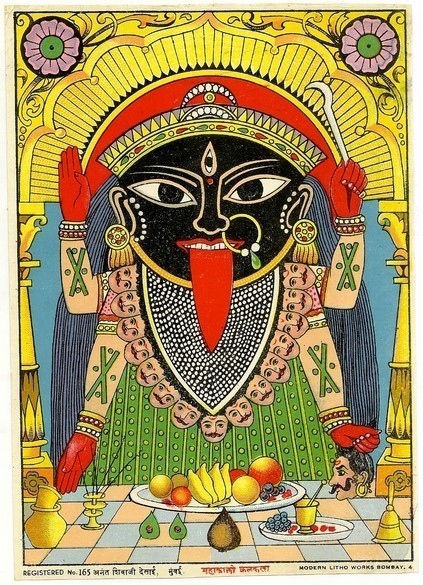

Indian literature and drama refer back constantly to the two concomitants of rasa (emotive essence) and bhava (emotive mood) which lie at the core of artistic creativity. This induced state of aesthetic appreciation is to be relished by a saha-hridaya, or a sensitized spectator. Rasa is a polyvalent word that means taste, flavour, sap, curative agent, relish, essence, aesthetic rapture and much else besides.

At its heart, rasa theory associates tasting with aesthetics on the basis of the physicality of emotions and concinnated ingredients that complex tastes and aesthetic moods demand. Further, it accommodates the double helix of artistic adventure: the artist abetted by empowered readers who ‘complete’ the work by adding to it their rasa of appreciation. The parallel to contemporary approaches to literary theory and aesthetics is evident.

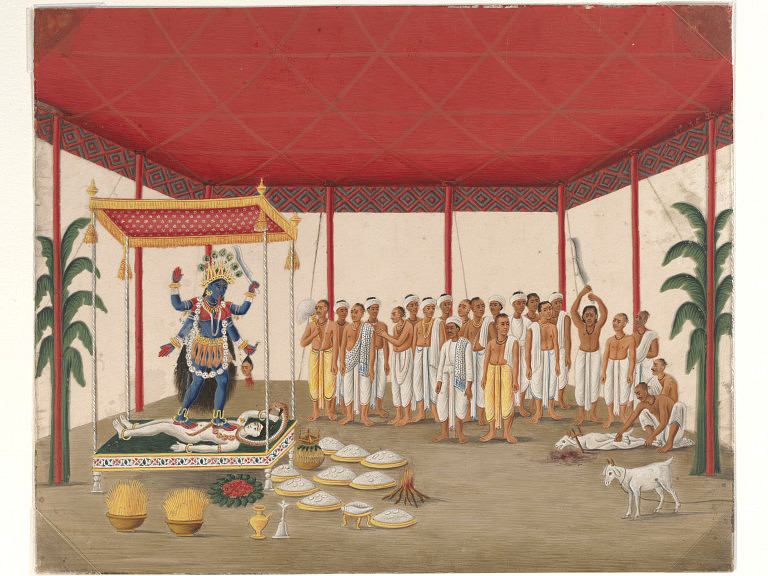

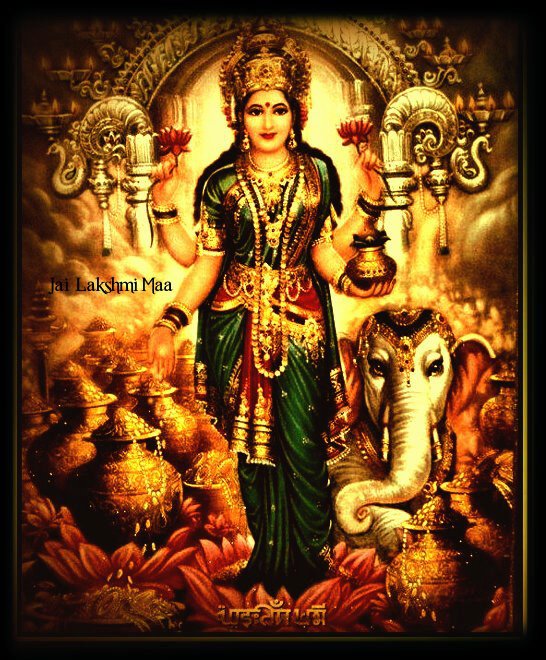

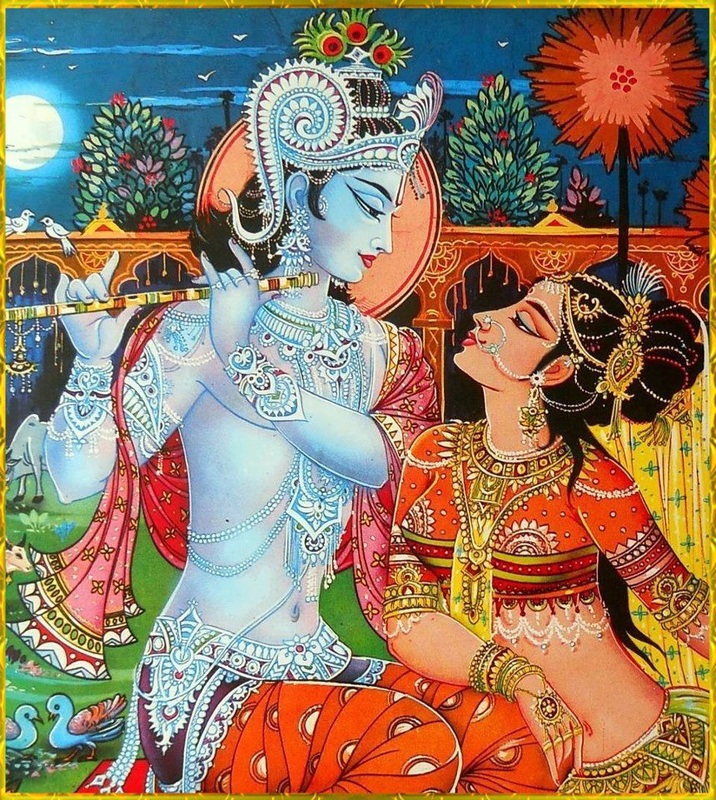

A saha-hridaya is literally one who shares the heart. The nine emotions, the navarasa, are sukhadukhatmak, evoking both pleasure and pain. Five of the rasas, sringar, hasya, veera, adbhuta and shanta, are joyous, while the other four, karuna, raudra, bhayanaka and vibhatsa, evoke pathos, anger, terror and revulsion.

The theory of rasa began with the Sanskrit text of the Natya Shastra, where eight bhavas were first described. The ninth bhava of the evolving navarasa is the shantam bhava of peace, equilibrium and praxis. Two more fundamental moods, of vatsalya or maternal love and bhakti or devotion were subsequently added to this lexicon.

The grammarians and theologians of Sanskrit poetics and scholarship were masters of analysis and cataloguing. The clarity and rigour of these classifications was subjected to even further hair-splitting analysis and pedantry, in time often leading to a dogmatic overstatement and obfuscation. But the underlying concept of the rasa and the rasika, and of the navarasas remained an underpinning of aesthetic activity, fruitful to its traditions and roots.

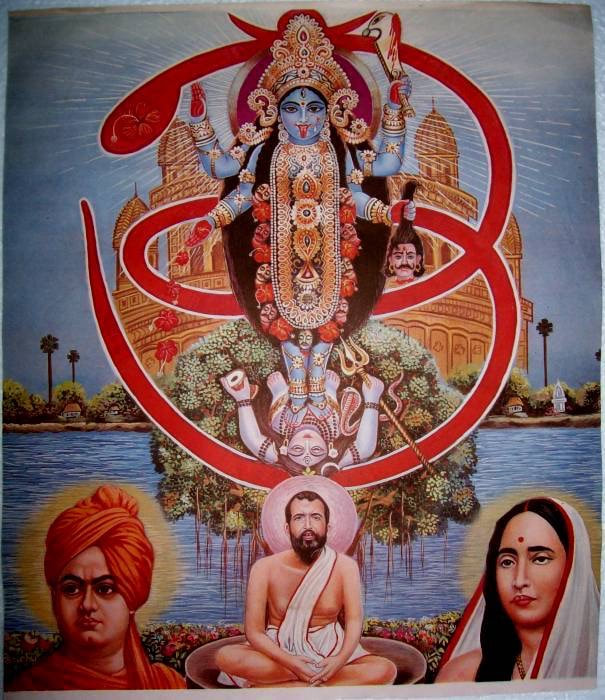

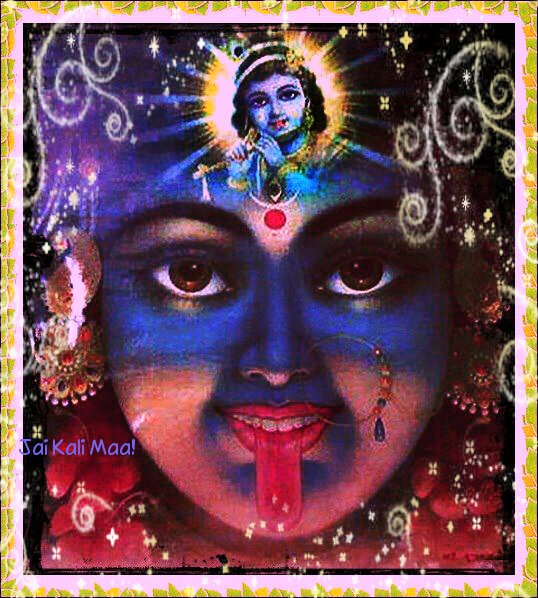

Rasa, or intense aesthetic pleasure, is the crucial element that illuminates the rigorously defined theories of Indian literary and artistic appreciation. Poetic intuition awakens the mystic third eye, the trilochana, allowing the creative mind to access both the past and the future through the trance-like state of higher understanding. This aesthetic pleasure is shared with fellow aesthetes, rasikas, or saha-hridayas who reach a similar state of heightened joy and perception by sharing the artist’s creation, which could be literary, musical or graphic.

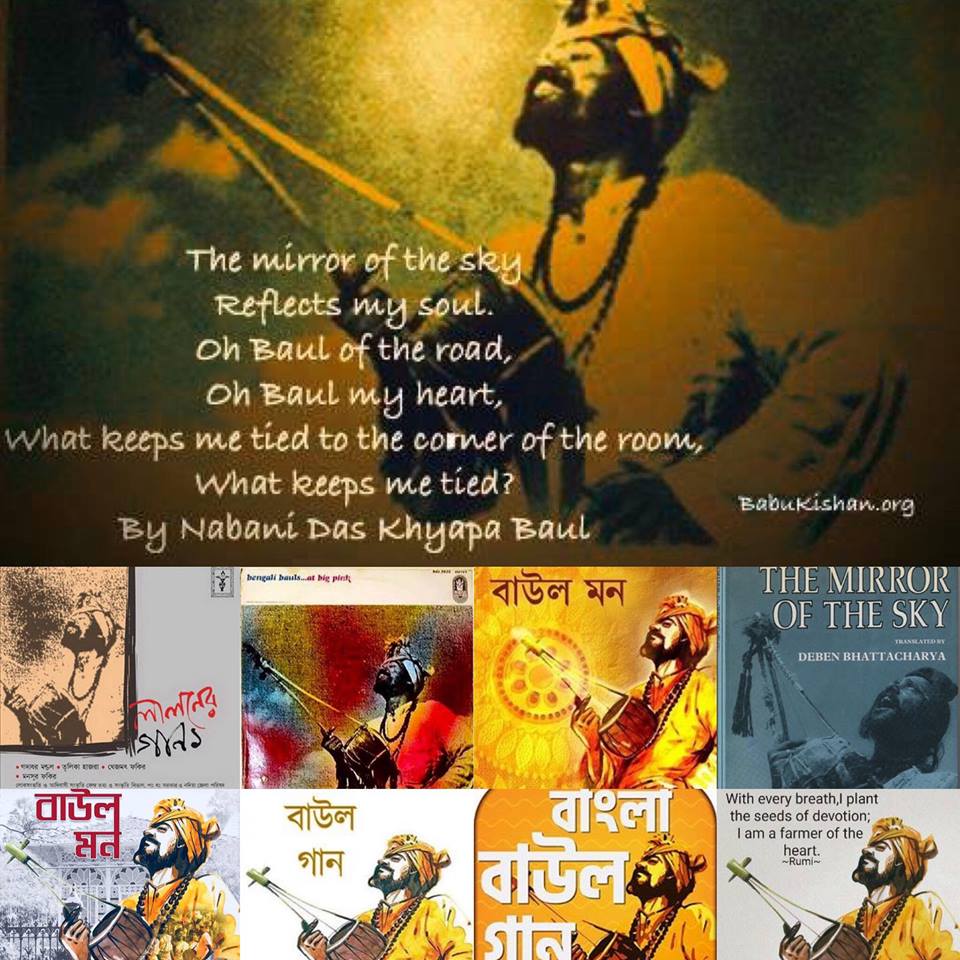

The theory of rasa is still contained in the intangible scaffolding of much of Indian and, occasionally, even South Asian classical and popular expression, be it visual, graphic, dramatic or literary representation.

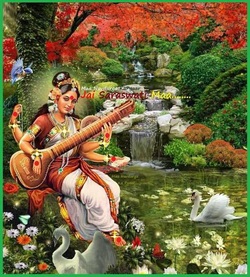

This module of diverse essays examines the layered heritage of the Fifth Veda in a contemporary light, and its significance. It searches patterns and insights to illuminate the persistence of memory in creative and artistic responses. Scrutinising submerged idiom, hidden metaphors and iconic continuities through the contradictions of Bollywood and art films, contemporary music and literature, it studies the stream of rasa that flows through select artistic visions like the mythical subterranean Saraswati River.

The module also contains essays that deflect this theory, reject and focus on artistic revolutions, suggesting that others too appropriated and/or discarded the undoubtedly elitist theory. Finally, it acts as a sampler to the thinking of artists and scholars on the rich rubric of the navarasas.

Investigating cultural roots and heritage is important for both the intuitive and empirical understanding of creative experience. It is through the continued assertions, or willful negations of these persistent ideas that we can more fully appreciate the evolving metatext of the millennium.

With this module, we seek to reach out to a new generation of readers, rasikas and saha-hridayas to, if possible, renew the understanding and potentials of the Fifth Veda.

https://www.sahapedia.org/rapture-rasa-and-its-re-enactments-subcontinental-aesthetics-narratives-of-practice?utm_source=sendinblue&utm_campaign=Sahapedia_Newsletter__November&utm_medium=email&fbclid=IwAR2dmzo3Ji_CmzNWu7sy1eBicLEK1VjbpcfnE9URKPlBNgMZT6yi-aqEH2A

RSS Feed

RSS Feed